Sheelagh Capendale, an expert in data

visualization, whose work has been revolutionary in exploring how researchers

investigate human behaviors in computer science, refers to her work as

“observation”. She claims that she works in science, but she learned to observe

in her background as an artist. She describes her experience as a young art

student, in her first photography course where the instructor gave the

excruciating assignment of asking students to photograph a blank wall; due in

three hours. She refers to the process as a painful lesson in observation, that

it wasn’t until after 2.5 hours of studying that wall, that the photos started

to emerge. That after hours of looking, she finally began to “see”.

Interestingly, she claims that she takes this same skill, the ability to “see”,

into her work as a researcher. That this skill is as useful in her career as an

internationally recognized scientist. Here, instead of photographing a wall,

she observes human behavior. She observes how domain experts, and (at times)

non-experts use visualizations of data. She uses multiple methodologies to

assist her in her observation: quantitative qualitative methods, established

and new. Even though this work is considered science, she uses the same skills

developed as an artist. Here I argue that this act of “observation” is a

learnable skill that and that adopting the posture of observation is admirable

across disciplines, and in particular, I focus its application in the practice

and theory of architecture.

Architecture is undergoing a paradigm

shift. This shift is likely propelled by post-modernism, a data revolution, new

modernism and a mass cultural shift towards pluralism, all of which is further

bolstered by the ubiquity of social media and the communication age. This shift

parallels the conceptual leap required of scientists in the centuries following

Galileo’s declaration that the earth is not the center of the universe. The

term “human-centered design” is not coincidental. For centuries, architects

have not questioned the assumption that their perception of the universe (no

matter how altruistic, or well-meaning) is the center of their inspiration. And

here it is folks: it is not.

In my experience, the mainstream of

architectural approaches do well at observing inanimate objects. Architecture

theory focuses on materiality, the generation of form and expression the poetic

as a spiritual marriage of idea and expression that will somehow inspire and

elevate civilization through a universal experience of the architecture as

expression. Louis Khan asked “what does the brick want to be?” Architects

ponder the nature of materials as a contemplative, expressive, exploration of

the emotive experience of texture, shape, and form. The power of form to

express the poetic is a well explored topic in architecture schools. I feel this has resulted in many architects

who have an uncanny level of skill and ingenuity with materials and an ability

to consciously manipulate the emotive, experiential effects of space, form and

visual information. As researchers, this same approach is manifested in the

philosophical approach of phenomenology. An approach that highlights and

emphasizes the bias of the observer. The personal, self-reflective experience

of space is the source of artistic inspiration, and the center (or starting

place) of knowledge. This is where, as I see it, the trajectory of

architectural theory has taken us. The architect at the center. A

self-reflective expert, who then projects his inspiration on the world through

his expression of experience through form.

While acknowledging bias is part of

the process of becoming a great observer, it is not the end point. True

observation is deeply concerned with understanding and learning the reality of

what lies beyond our own bias. Confirmation bias is a knowledge killer. The

reproducibility crisis in psychology research attests to the challenge of

assuming we know without double (or even better, triple checking). The dangers

of this can lead to mistakes. Mistakes made by people who are making decisions

about cities, hospitals, medicines, health, life and death. It’s not good.

In data visualization there is a

concept called “change blindness”. It is a well-researched phenomenon where

people will often not see something if they don’t expect it. In studies where

researchers replace actors without any hint of the replacement, or where there

is a visual change in an image or scene, participants who are focused on

something else, or not expecting the change - will not actually see it. The type

of observation Sheelagh Carpendale is referring to is one which uses all

available tools to overcome the natural tendency of change blindness. It is

being a good observer, acknowledging bias, grappling with one’s own ego to get

beyond what we think is in front of us - and ACTUALLY SEE WHAT IS THERE. It is

a personal practice as well as adopting iterative, painstaking, rigorous,

research methodologies to ensure our observations are as close a model of

reality as we can hope for. Interestingly, while artists might be excellent at

the former processes of self-reflection and emotive expression, scientists have

well established methods for the latter. Although, as one moves further into

the understanding observation, these divisions between disciplines is less

useful. Artist, researcher, designer or scientist, the act of well-honed

observation is critical to acquiring knowledge, understanding and innovation.

You may assume that true and great

inspiration comes from the ethos of the artist, designer or great scientist.

One may think this, because it is the narrative we have been told. The master

(male) artist, the great (male) architect, the genius (male) scientist, who

ponders existence, and finds inspiration through some magical moment of

inspiration. But this narrative, is, of course not true. Inspiration and

innovation is arrived at through a well-honed practice; that includes

self-reflection, observation, craft, time, pain and struggle. This is inspired

by a sincere and profound sense of curiosity. And though methods and objects

may differ, this process is the same whether a person is a scientist,

researcher, artist or designer.

All this said, architecture is a

deeply inquisitive practice and architects themselves are altruistic and

humble...or at least the ones I know are. Contrary to what I have just said,

architectural practice also has a long history of using data and methods of

inquiry in their practice, although this process has become periphery. While

the discipline has focused on the generation of form, one might wonder where

the “humans” are. Vitruvius in this seminal work about the philosophy or

architecture talks about the three pillars of architecture: beauty, function

and structure. While much of architecture research has highlighted the expressive

nature of structure and beauty, the practice of human observation responds to

the pillar of function. And while architecture research has yet to evolve into

the established academic institution familiar to the sciences, the discipline

has persisted by often disseminating new knowledge in neighboring disciplines

such as urban planning, geography, philosophy and design theory. While this

makes it difficult to define what architecture research is, it points to a

large amount of relevant, data-driven research that has impacted architectural

design culture and practice for generations... (this all leads to a discussion that I plan to continue to write about...stay tuned :) on

using spatial data in design, the love/hate relationship with environmental

psychology, the somewhat irrational fear of science on behalf of architects,

and awesome new relevant work that is generating new technologies and

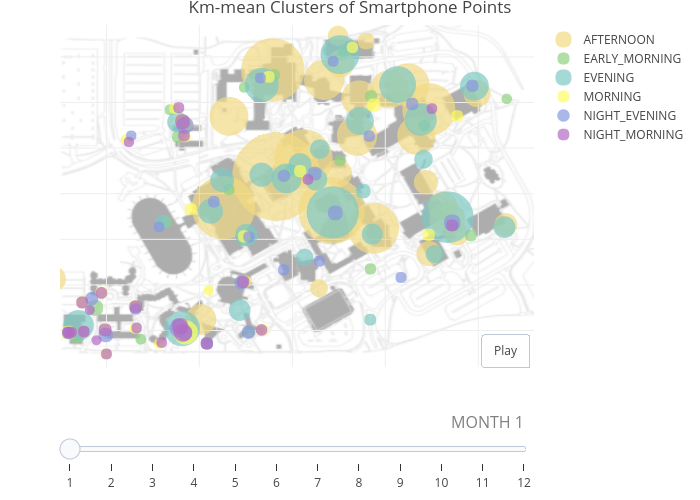

methods for understanding complex behavior patterns using hierarchical

regression modeling and spatial data)

Architecture research needs to

incorporate rigorous empirical methods using quantitative data. Sheelagh

Carpendale is celebrated for her work in advocating for using multiple

mixed-methods in data visualization. This is not an argument for which method

is better. The nature of the inquiry and the research question dictates the

best method to adopt. I argue that architects and architecture researchers

should follow a similar trajectory as human computer interaction, and data

visualization - while bringing a unique-to-architecture layer of design

expertise. And while architectural research has primarily focused on

qualitative processes of inquiry, it is time for architectural design researchers to balance out

their practices and learn how to use (or at least benefit from) the tools of quantitative research. This

balance of methodology will help tip the balance of architecture research

towards the objectives of “human centered” design.